Dynamic resolution scaling in Monogame/XNA

Dynamic resolution scaling (DRS) is a functionality used to deliver a better frame rate in 3D rendering at cost of resolution. At moments which are taxing to render, the resolution is automatically dropped to improve performance. When the time needed to render the scene becomes shorter, the resolution is increased back to native. Potentially, it can be used also for dynamic supersampling. If DRS is new to you, I suggest to view the excellent video by Digital Foundry given below.

To implement this functionality you need to have a basic experience with using RenderTargets. Even though I implemented DRS in MonoGame/XNA, the concept itself and thus this tutorial can be easily used with other frameworks too.

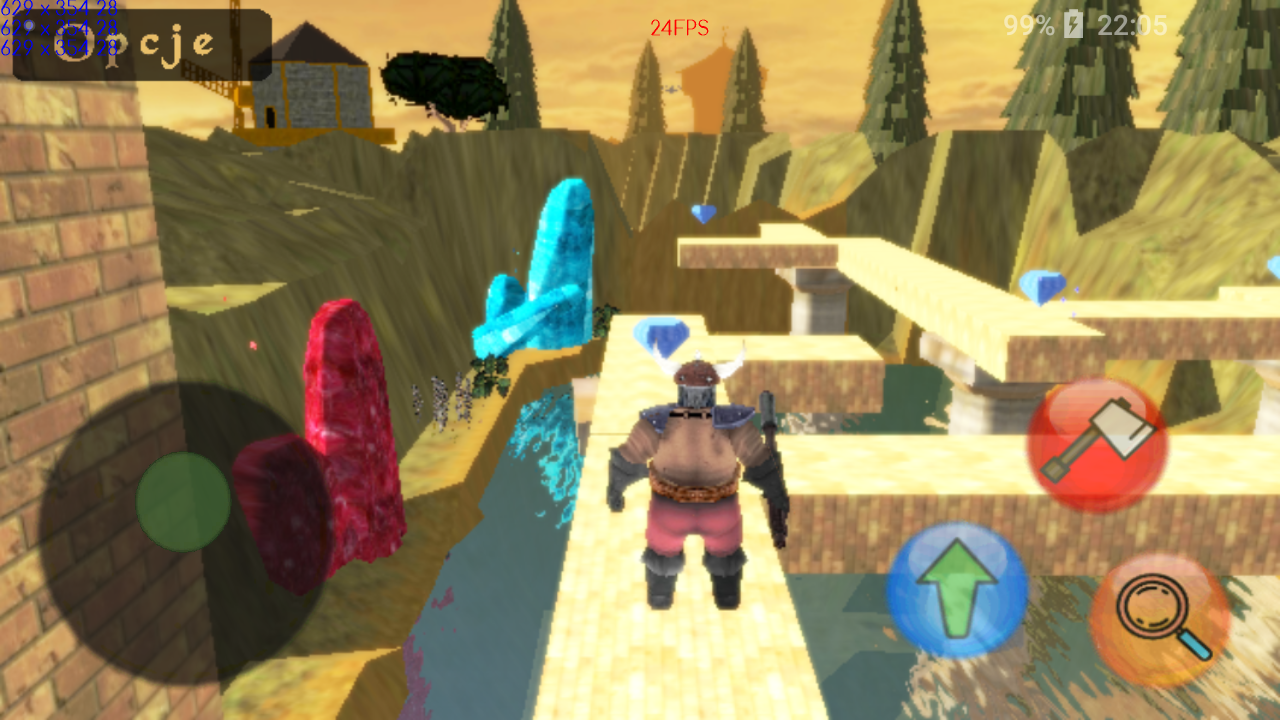

I implemented this technique in a small game I did together with my friend some time ago. It is free and it has no ads, so if you have Android phone please feel free to check it and see by yourself how the DRS performs: Vorn’s Adventure

First, let’s analyze how DRS works and what are the downsides coming from its implementation.

At first, the game starts with native resolution equal to 1280x720.

Then, after a while, when new and taxing area becomes visible, it goes down to intermediate 1227x691 resolution.

Now, the camera spans over a huge area which is very taxing. The water renders reflections, hence some models are rendered more than once. Therefore, the resolution goes to lowest possible equal to 534x300 to keep reasonable performance.

The next scene is less taxing to draw. There is a smaller number of complex models, albeit the reflections are still drawn. The resolution improves to 628x354.

Finally, when only a few models are visible, the resolution goes back to maximal, native 1280x720.

The downsides of DRS are:

• Obviously worse visuals when resolution goes down, but clearly visible only when the resolution drops are significant

• When the resolution drop occurs, the actual process is easily noticable to player on all edges. This can be mitigated with usage of antialiasing.

• The smaller resolution may not always fix the problems with drawing performance. The number of draw calls for features visible on the scene may create a bottleneck on CPU side, what is actually very common on mobiles.

• Reallocation of RenderTargets takes some time. I think though that it can be mitigated by using ViewPorts if this becomes a problem.

Now, let’s get to the actual implementation. The first question to be answered is how to actually determine the need for changing the resolution. The obvious idea – frames per second (FPS) – is not the best solution as it ignores all factors that can limit performance. Hence, instead it makes more sense to calculate the time it takes to process the Draw() function. This is still not the best metric, as the problem may lie for example in the number of draw calls what means that CPU bottlenecks the performance. However, I won’t say that’s the definite solution – there might be more variables in this equation in play. Perhaps you can share a better idea in comments?

I decided to change the factor from the last Draw() call to the minimum of last N Draw() calls due to the uneven CPU core frequencies in newer Android devices. Let’s take a look at two Android devices I’m using for tests. The first is an old Samsung Galaxy A3 from 2014 with miserable Quad-Core 1.2 Ghz. The second one is much newer Sony XA1 with Octa-Core CPU – the thing is, four CPU cores have a frequency 2.3 Ghz and the other four cores have performance of 1.6 Ghz. While the first device is really slow, you can expect that it will maintain consistent performance across threads. On the other hand, the second device may use either a fast 2.3 Ghz core or a slow 1.6 Ghz core for a thread leaving no control for the developer. It’s not a fact that should be downplayed, as in comparison the turboboost on modern desktop CPUs creates a far smaller performance differential than in the cited case. Coming back to the Draw() calls: in case of uneven CPU performance, relying on only the last Draw() call would be insufficient – we do not know whether this Draw() call landed on the fast or slow core. This would end up in continuous changes in Draw() call speeds and as a result possibly continuous fluctuations in screen resolution what would be an unpleasant experience for the end-user. I will refer to the measured minimum time for draw calls (in milliseconds) by using the variable minDrawTime.

Next, we need to establish what is our target performance. To do this, we need to calculate what would be the frame time in our scenario. For 60 FPS that would be 1/60th of a second, so 16.6 ms. For our case, let’s assume we are targeting a more achievable 30 FPS, hence 33.3 ms. Here, I suggest to cheat a little and force a bit more demanding performance criteria to avoid unnecessary fluctuations in resolution scaling. So, instead of 33.3 ms, by rule of thumb, let’s target 29 ms. I will refer to this target performance for draw call (again in milliseconds) by using the variable TargetDrawTime (upper case as it is a constant value).

Now, having these values defined, it is time to derive our resolution scaling factor. Let’s give it a name currentResolutionScaleRatio. Since we are starting with the native resolution, it should obviously have a starting value equal to 1f.

Last thing our algorithm requires, is the resolution change factor – a magic value, that will be used to determine how fast the dynamic scaling should be. I suggest to play a little bit with different values (smaller are better for development and bug fixing). Again by a rule of thumb, that will be 0.2f in my case. I will refer to this factor by using the constant variable ResolutionChangeFactor.

So, having all these different variables, the resulting formula is:

var delta = ResolutionChangeFactor * currentResolutionScaleRatio *

((TargetDrawTime - minDrawTime) / TargetDrawTime);

currentResolutionScaleRatio += delta;

The currentResolutionScaleRatio shall be then applied to the RenderTarget that is used for rendering. Please note, you must first dispose the already existing RenderTarget and allocate the new one. This obviously has additional penalty on CPU performance, albeit in my tests it proven to be small enough that I can allow to reallocate 4 RenderTargets when using deferred rendering. I believe it can be eventually mitigated by using ViewPorts.

Comments